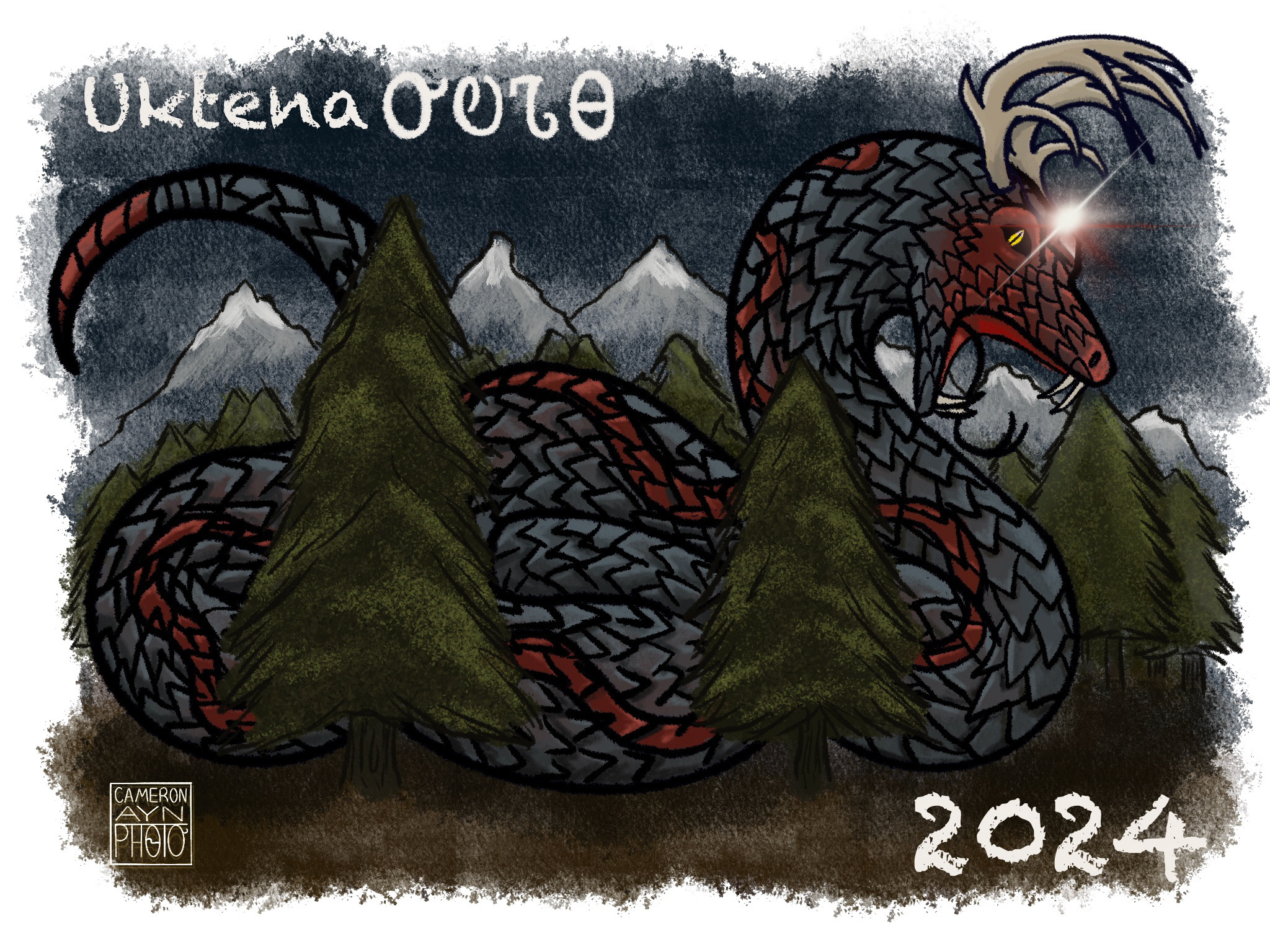

Introducing "Whispers of the Ancestors": A Collection of Cherokee Blanket Designs

Each design in our collection is meticulously crafted to capture the essence of Cherokee stories, myths, and legends. From the majestic mountains to the flowing rivers, from the animals of the forest to the spirits of the sky, every pattern holds a piece of Cherokee history and symbolism.

Not only are these blankets a stunning addition to any home decor, but they also serve as a reminder of the importance of preserving and honoring Indigenous cultures. With each purchase, you're not just acquiring a blanket – you're supporting Indigenous artisans and communities, ensuring that their stories continue to be told for generations to come.

Experience the beauty, history, and spirit of the Cherokee people with "Whispers of the Ancestors." Let these blankets wrap you in warmth and wisdom as you embark on a journey through Cherokee heritage.

Read the stories these designs were inspired from below.

Atagahi ᎠᎳᎦᎯ

The Enchanted Lake Design

The Atagahi, or Enchanted Lake design, draws inspiration from a Cherokee legend. It depicts a hidden lake, guarded by animals, known for granting healing to those who vigilantly pray and fast through the night. This design, based on James Mooney's detailed account in "Myths of the Cherokees" (1900), was originally crafted as a blanket, intended as a heartfelt gift to envelop loved ones in need of healing.

Below is the story from "Myths of the Cherokees"

ATAGÂ′HĬ, THE ENCHANTED LAKE

Westward from the headwaters of Oconaluftee river, in the wildest depths of the Great Smoky mountains, which form the line between North Carolina and Tennessee, is the enchanted lake of Atagâ′hĭ, “Gall place.” Although all the Cherokee know that it is there, no one has ever seen it, for the way is so difficult that only the animals know how to reach it. Should a stray hunter come near the place he would know of it by the whirring sound of the thousands of wild ducks flying about the lake, but on reaching the spot he would find only a dry flat, without bird or animal or blade of grass, unless he had first sharpened his spiritual vision by prayer and fasting and an all-night vigil.

Because it is not seen, some people think the lake has dried up long ago, but this is not true. To one who had kept watch and fast through the night it would appear at daybreak as a wide-extending but shallow sheet of purple water, fed by springs spouting from the high cliffs around. In the water are all kinds of fish and reptiles, and swimming upon the surface or flying overhead are great flocks of ducks and pigeons, while all about the shores are bear tracks crossing in every direction. It is the medicine lake of the birds and animals, and whenever a bear is wounded by the hunters he makes his way through the woods to this lake and plunges into the water, and when he comes out upon the other side his wounds are healed. For this reason the animals keep the lake invisible to the hunter.

Unehlanvhi ᎤᏁᏝᏅᎯ

Creation Story blanket

The second design in the "Whispers of Our Ancestors" blanket series – the "Unehlanvhi: Creation Blanket." This design draws inspiration from the Cherokee creation story, where five sacred trees—laurel, spruce, pine, cedar, and holly—along with the owl and panther, remained awake for the seven days of creation.

I’d love for you to explore this design and discover the meaning behind it.

1. HOW THE WORLD WAS MADE

The earth is a great island floating in a sea of water, and suspended at each of the four cardinal points by a cord hanging down from the sky vault, which is of solid rock. When the world grows old and worn out, the people will die and the cords will break and let the earth sink down into the ocean, and all will be water again. The Indians are afraid of this.

When all was water, the animals were above in Gălûñ′lătĭ, beyond the arch; but it was very much crowded, and they were wanting more room. They wondered what was below the water, and at last Dâyuni′sĭ, “Beaver’s Grandchild,” the little Water-beetle, offered to go and see if it could learn. It darted in every direction over the surface of the water, but could find no firm place to rest. Then it dived to the bottom and came up with some soft mud, which began to grow and spread on every side until it became the island which we call the earth. It was afterward fastened to the sky with four cords, but no one remembers who did this.

At first the earth was flat and very soft and wet. The animals were anxious to get down, and sent out different birds to see if it was yet dry, but they found no place to alight and came back again to Gălûñ′lătĭ. At last it seemed to be time, and they sent out the Buzzard and told him to go and make ready for them. This was the Great Buzzard, the father of all the buzzards we see now. He flew all over the earth, low down near the ground, and it was still soft. When he reached the Cherokee country, he was very tired, and his wings began to flap and strike the ground, and wherever they struck the earth there was a valley, and where they turned up again there was a mountain. When the animals above saw this, they were afraid that the whole world would be mountains, so they called him back, but the Cherokee country remains full of mountains to this day.

When the earth was dry and the animals came down, it was still dark, so they got the sun and set it in a track to go every day across the island from east to west, just overhead. It was too hot this way, and Tsiska′gĭlĭ′, the Red Crawfish, had his shell scorched a bright red, so that his meat was spoiled; and the Cherokee do not eat it.

The conjurers put the sun another hand-breadth higher in the air, but it was still too hot. They raised it another time, and another, until it was seven handbreadths high and just under the sky arch. Then it was right, and they left it so. This is why the conjurers call the highest place Gûlkwâ′gine Di′gălûñ′lătiyûñ′, “the seventh height,” because it is seven hand-breadths above the earth. Every day the sun goes along under this arch, and returns at night on the upper side to the starting place.

There is another world under this, and it is like ours in everything—animals, plants, and people—save that the seasons are different. The streams that come down from the mountains are the trails by which we reach this underworld, and the springs at their heads are the doorways by which we enter it, but to do this one must fast and go to water and have one of the underground people for a guide. We know that the seasons in the underworld are different from ours, because the water in the springs is always warmer in winter and cooler in summer than the outer air.

When the animals and plants were first made—we do not know by whom—they were told to watch and keep awake for seven nights, just as young men now fast and keep awake when they pray to their medicine. They tried to do this, and nearly all were awake through the first night, but the next night several dropped off to sleep, and the third night others were asleep, and then others, until, on the seventh night, of all the animals only the owl, the panther, and one or two more were still awake. To these were given the power to see and to go about in the dark, and to make prey of the birds and animals which must sleep at night. Of the trees only the cedar, the pine, the spruce, the holly, and the laurel were awake to the end, and to them it was given to be always green and to be greatest for medicine, but to the others it was said: “Because you have not endured to the end you shall lose your hair every winter.”

Men came after the animals and plants. At first there were only a brother and sister until he struck her with a fish and told her to multiply, and so it was. In seven days a child was born to her, and thereafter every seven days another, and they increased very fast until there was danger that the world could not keep them. Then it was made that a woman should have only one child in a year, and it has been so ever since.

Ani ᎠᏂ

Strawberry Blanket Design

ORIGIN OF STRAWBERRIES

When the first man was created and a mate was given to him, they lived together very happily for a time, but then began to quarrel, until at last the woman left her husband and started off toward Nûñdâgûñ′yĭ, the Sun land, in the east. The man followed alone and grieving, but the woman kept on steadily ahead and never looked behind, until Une′ʻlănûñ′hĭ, the great Apportioner (the Sun), took pity on him and asked him if he was still angry with his wife. He said he was not, and Une′ʻlănûñ′hĭ then asked him if he would like to have her back again, to which he eagerly answered yes.

So Une′ʻlănûñ′hĭ caused a patch of the finest ripe huckleberries to spring up along the path in front of the woman, but she passed by without paying any attention to them. Farther on he put a clump of blackberries, but these also she refused to notice. Other fruits, one, two, and three, and then some trees covered with beautiful red service berries, were placed beside the path to tempt her, but she still went on until suddenly she saw in front a patch of large ripe strawberries, the first ever known. She stooped to gather a few to eat, and as she picked them she chanced to turn her face to the west, and at once the memory of her husband came back to her and she found herself unable to go on. She sat down, but the longer she waited the stronger became her desire for her husband, and at last she gathered a bunch of the finest berries and started back along the path to give them to him. He met her kindly and they went home together. [260]

ᏅᏬᏘ nvwoti

Medicine Design

ORIGIN OF DISEASE AND MEDICINE

In the old days the beasts, birds, fishes, insects, and plants could all talk, and they and the people lived together in peace and friendship. But as time went on the people increased so rapidly that their settlements spread over the whole earth, and the poor animals found themselves beginning to be cramped for room. This was bad enough, but to make it worse Man invented bows, knives, blowguns, spears, and hooks, and began to slaughter the larger animals, birds, and fishes for their flesh or their skins, while the smaller creatures, such as the frogs and worms, were crushed and trodden upon without thought, out of pure carelessness or contempt. So the animals resolved to consult upon measures for their common safety.

The Bears were the first to meet in council in their townhouse under Kuwâ′hĭ mountain, the “Mulberry place,” and the old White Bear chief presided. After each in turn had complained of the way in which Man killed their friends, ate their flesh, and used their skins for his own purposes, it was decided to begin war at once against him. Some one asked what weapons Man used to destroy them. “Bows and arrows, of course,” cried all the Bears in chorus. “And what are they made of?” was the next question. “The bow of wood, and the string of our entrails,” replied one of the Bears. It was then proposed that they make a bow and some arrows and see if they could not use the same weapons against Man himself. So one Bear got a nice piece of locust wood and another sacrificed himself for the good of the rest in order to furnish a piece of his entrails for the string. But when everything was ready and the first Bear stepped up to make the trial, it was found that in letting the arrow fly after drawing back the bow, his long claws caught the string and spoiled the shot. This was annoying, but some one suggested that they might trim his claws, which was accordingly done, and on a second trial it was found that the arrow went straight to the mark. But here the chief, the old White Bear, objected, saying it was necessary that they should have long claws in order to be able to climb trees. “One of us has already died to furnish the bow-string, and if we now cut off our claws we must all starve together. It is better to trust to the teeth and claws that nature gave us, for it is plain that man’s weapons were not intended for us.”

No one could think of any better plan, so the old chief dismissed the council and the Bears dispersed to the woods and thickets without having concerted any way to prevent the increase of the human race. Had the result of the council been otherwise, we should now be at war with the Bears, but as it is, the hunter does not even ask the Bear’s pardon when he kills one.

The Deer next held a council under their chief, the Little Deer, and after some talk decided to send rheumatism to every hunter who should[251]kill one of them unless he took care to ask their pardon for the offense. They sent notice of their decision to the nearest settlement of Indians and told them at the same time what to do when necessity forced them to kill one of the Deer tribe. Now, whenever the hunter shoots a Deer, the Little Deer, who is swift as the wind and can not be wounded, runs quickly up to the spot and, bending over the blood-stains, asks the spirit of the Deer if it has heard the prayer of the hunter for pardon. If the reply be “Yes,” all is well, and the Little Deer goes on his way; but if the reply be “No,” he follows on the trail of the hunter, guided by the drops of blood on the ground, until he arrives at his cabin in the settlement, when the Little Deer enters invisibly and strikes the hunter with rheumatism, so that he becomes at once a helpless cripple. No hunter who has regard for his health ever fails to ask pardon of the Deer for killing it, although some hunters who have not learned the prayer may try to turn aside the Little Deer from his pursuit by building a fire behind them in the trail.

Next came the Fishes and Reptiles, who had their own complaints against Man. They held their council together and determined to make their victims dream of snakes twining about them in slimy folds and blowing foul breath in their faces, or to make them dream of eating raw or decaying fish, so that they would lose appetite, sicken, and die. This is why people dream about snakes and fish.

Finally the Birds, Insects, and smaller animals came together for the same purpose, and the Grubworm was chief of the council. It was decided that each in turn should give an opinion, and then they would vote on the question as to whether or not Man was guilty. Seven votes should be enough to condemn him. One after another denounced Man’s cruelty and injustice toward the other animals and voted in favor of his death. The Frog spoke first, saying: “We must do something to check the increase of the race, or people will become so numerous that we shall be crowded from off the earth. See how they have kicked me about because I’m ugly, as they say, until my back is covered with sores;” and here he showed the spots on his skin. Next came the Bird—no one remembers now which one it was—who condemned Man “because he burns my feet off,” meaning the way in which the hunter barbecues birds by impaling them on a stick set over the fire, so that their feathers and tender feet are singed off. Others followed in the same strain. The Ground-squirrel alone ventured to say a good word for Man, who seldom hurt him because he was so small, but this made the others so angry that they fell upon the Ground-squirrel and tore him with their claws, and the stripes are on his back to this day.

They began then to devise and name so many new diseases, one after another, that had not their invention at last failed them, no one of the human race would have been able to survive. The Grubworm grew [252]constantly more pleased as the name of each disease was called off, until at last they reached the end of the list, when some one proposed to make menstruation sometimes fatal to women. On this he rose up in his place and cried: “Wadâñ′! [Thanks!] I’m glad some more of them will die, for they are getting so thick that they tread on me.” The thought fairly made him shake with joy, so that he fell over backward and could not get on his feet again, but had to wriggle off on his back, as the Grubworm has done ever since.

When the Plants, who were friendly to Man, heard what had been done by the animals, they determined to defeat the latters’ evil designs. Each Tree, Shrub, and Herb, down even to the Grasses and Mosses, agreed to furnish a cure for some one of the diseases named, and each said: “I shall appear to help Man when he calls upon me in his need.” Thus came medicine; and the plants, every one of which has its use if we only knew it, furnish the remedy to counteract the evil wrought by the revengeful animals. Even weeds were made for some good purpose, which we must find out for ourselves. When the doctor does not know what medicine to use for a sick man the spirit of the plant tells him.